And a fantastic portrait of the kind of craven lickspittle that runs the US. The way in which once you have gained entrance into the magic circle and proven that you have no ideology other than an unquestioning deference to power and narrow self interest, you have a life-long career in which it is impossible to fail.

Christopher Hitchens felt that Isaacson’s fealty to “the tradition of New York-Washington ‘objectivity’” led him to grossly euphemize Kissinger’s war crimes. Isaacson, Hitchens wrote in the London Review of Books, “moves in a world where the worst that is often said of some near-genocidal policy is that it sends the wrong ‘signal.’”

Isaacson’s magnanimity was less usefully deployed at CNN, where he was made CEO in the summer of 2001. He arrived at a network under attack from an ascendant Fox News, which had been pitched by Rupert Murdoch as an alternative to the hegemony of the liberal media. Isaacson aimed for principled impartiality — or he played both sides, depending on how you look at it. One of his first moves as chairman was to meet with Republican lawmakers to discuss how the network could cover conservative perspectives with balance. The strategy backfired. Liberal viewers thought Isaacson was pandering to the right, while conservatives still preferred Fox, particularly after 9/11, when Roger Ailes expertly appealed to patriotic bloodlust. In 2002, Fox eclipsed CNN in the ratings, and Isaacson left the following year.

The tech scene was one that Isaacson was already familiar with and enamored by. In the 1990s, he had briefly left Time to work as the new media editor for Time Warner, where he helped develop Pathfinder.com, a web portal that aggregated content from across the media company. This early attempt at digital journalism failed, costing the company over a hundred million dollars. Isaacson was sent back to edit the magazine, where he satisfied his entrepreneurial urge by establishing a new section covering science and technology, with a focus on the wunderkinds of Silicon Valley.

After the da Vinci biography, Isaacson left the Aspen Institute, became a history professor at Tulane University, took a consulting role focusing on “technology and the new economy” at a global financial services firm, and launched a podcast in partnership with Dell called “Trailblazers,’’ which looked at “digital disruption and innovators using tech to enable human progress.” He also continued working in policy, something he had intermittently done for decades. (Isaacson advised the Bush administration on U.S.-Palestine relations, for example, and under Obama, he was appointed to the Defense Innovation Board.)

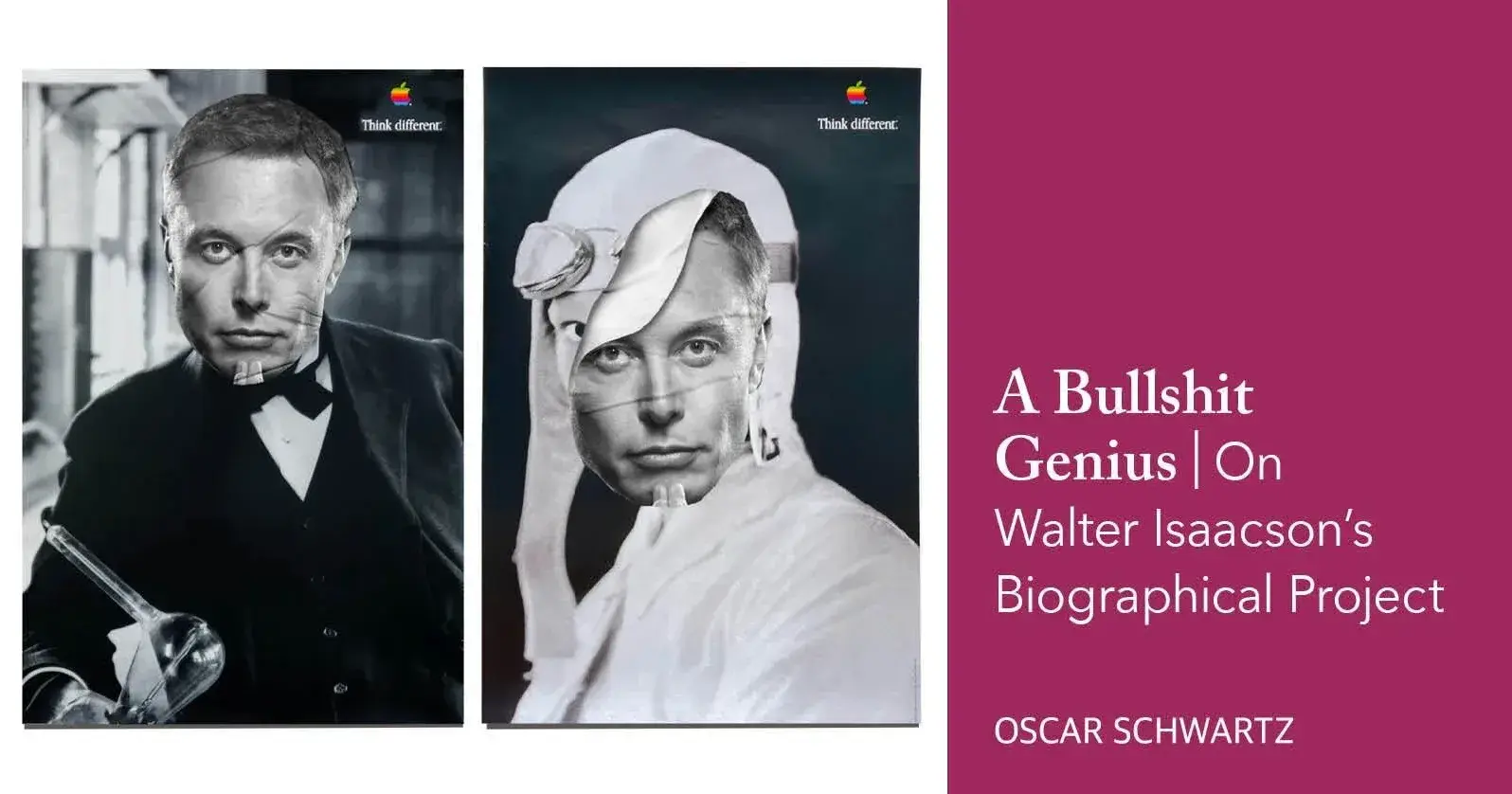

Like Jobs, Musk’s great talent is in self-mythologizing. He builds his cult of personality not around the guru-creative ideal, as Jobs did, but as a crazed, workaholic, alpha-male superhero: a manic Iron Man sending a Tesla Roadster into space. Isaacson credulously regurgitates Musk’s lore, just as he did in Jobs, recounting an anecdote in which Musk plays a game of Texas Hold ’Em and goes all in on every single hand — losing, doubling up — until he eventually wins. “It would be a theme in his life,” Isaacson writes. “Avoid taking chips off the table; keep risking them.”