Conclusions

This has been, by intention, a retrospective review of economic trends dating back to 1980. But most of us are interested, not just in where we’ve come from, but in where we’re going.

The ‘big factors’ that emerge from our retrospective analysis can be listed as follows.

-

Both the non-energy resource base and the ex-cost economic value of energy have been depleting markedly, trends greatly exacerbated by relentless increases in population numbers.

-

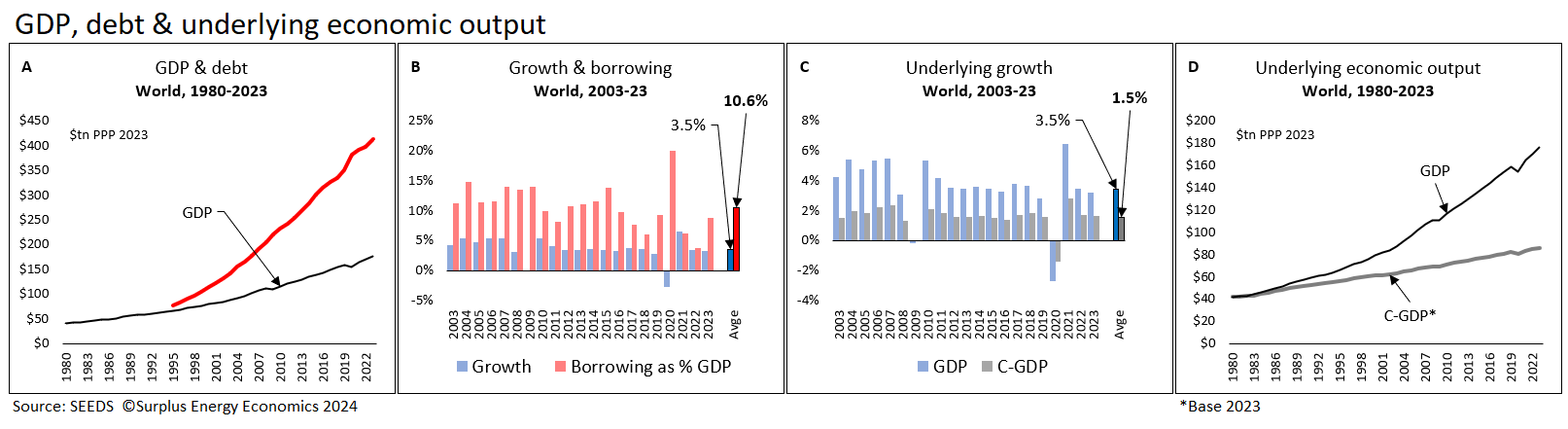

Most of the “growth” reported in financial aggregates has been cosmetic, a product of ignoring debt and other liabilities, disregarding ECoE, and excluding natural resource depletion from our measurement of economic output.

-

Four decades of reported “growth” have, in fact, seen material economic prosperity barely outperform the rate of growth in the global population.

These underlying trends are continuing. Comparing 2040 with 2023, we can expect the Energy Cost of Energy to rise by about 75%, and the conversion ratio of natural resources into economic value to continue to decrease. Significantly, aggregate energy production is likely to decline, with falls in fossil fuels output only partly offset by increases in the supply of renewables.

On this basis, the aggregate of material economic output is likely to fall by around 18%.

If population numbers continue to increase – albeit at a decelerating rate – the World’s average person is likely to be fully 27% less prosperous in 2040 than he or she is today. At the same time, the cost of necessities per capita is projected to be about 40% higher in 2040 than it is today.

As well as pushing the affordability of discretionary (non-essential) products and services sharply downwards, this trend will undermine the ability of households to support their enormously-expanded commitments to the financial system.

If past form is anything to go by, decision-makers, far from accepting actual economic reality and acting accordingly, are likely to carry on trying to stimulate the material economy with monetary tools.

On this basis, a “GFC II” sequel to the global financial crisis of 2008-09 has now been hard-wired into the system.

The decisions that we make are ours alone, but the effectiveness of our choices – financial, occupational, political, social and perhaps even geographical – can only be enhanced if we opt for facts in preference to myths.