Apologies for posting.

I should say by way of introductory remarks, that while this is an effort post, it is an effort post on a shitposting website, and thus ab initio a shitpost and therefore be taken in the correct spirit of levity in which it is intended. Don’t get my thread locked.

Recent discussion on here has touched on the moral status of the execution of the Romanov family by Bolsheviks ahead of the advancing White Army1. While not exactly of practical significance given how few of us have Royal Families locked up in our basement, it did reveal several significant, (sometimes severe) differences in the philosophical underpinnings of the posters on this website.

A Moral Communism

Moral status as such actually has very little to deal with communism/leftist (in the Marxian vein) in terms of it’s internal mechanism. Marx, Engels, Lenin, and the rest of that intellectual lineage2. famously thought very little of moral philosophy. A communist is thus entirely at liberty to dismiss this entire discussion as idealism, and observe that within a Marxist framework, there are no ‘good’ and ‘bad’, merely a historically deterministic sequence of class antagonisms that will eventually resolve in favor of the proletariat and thus choosing to be a communist is merely choosing to throw one’s hat in with the predetermined victors. This strand of amoral communism thus is not terribly interested in this discussion, and anyone here that adheres to that framework is excused from the discussion as having won the argument.

Given the rest of us do have moral considerations that prefigure our political beliefs, it’s necessary for us to sketch out at least a scaffolding for what moral commonalities leftists share before going further, lest we fall into a morass of fundamentally incompatible frameworks stemming from different axiomatic premises. Speaking from my own personal position, I ascribe to leftist political positions as they offer me the greatest promise of granting a comfortable and dignified existence to the largest number of people possible. That in of itself does not make a moral axiom though, as achieving a large amount of something is valueless if the individual components don’t themselves have value, and therefore, and a fundamental value informing my politics is the axiomatic value/sanctity of human life. So I am taking on as an assumption that generally speaking, want everyone to have dignified and comfortable lives3. If that position doesn’t more or less describe you, you are also excused as having won the argument.

Justifying Shooting a Tsesarevich in my Pajamas

Which brings us to the Romanovs. In keeping with 3. above, and considering the minor children of royals not culpable for the systematic injustices perpetrated under the dictatorship of their parents, we’ll limit our discussion here to the minors (Anastasia, and especially Alexei), though I think the general outline of the argument can be applied to pretty much all of the Tsar’s issue. The entirety of the family, along with their retinue, were bulleted and bayoneted in Yekaterinburg about 10 days before white occupied the city. In attempting to defend the legacy of one of the most politically successful socialist projects in history4., this action has largely been justified on the left. Examining the commonly proposed justifications in light of our moral principles finds them universally lacking.

- It was necessary in order to safeguard the immediate success of the revolution against an individual with claim to the throne.

This argument goes that while we do value human life and dignity, our efforts to maximize these will sometimes require that certain human lives be forfeit, essentially turning this into a trolley problem5.. This argument differs in an important aspect from the trolley problem in that the trolley problem consists of single moment in time with clearly articulable and certain outcomes given at the outset. Leaving Alexei alive was in no way certain to doom the revolution to failure of significant struggle, as he could have been maintained in custody, and ascribing such outsized influence on the course of political affairs to the life of a sickly 13 year old is a profoundly anti-materialist approach to history. History is replete with challenges to establish socialist authority6., none of which stemmed from claimants to the Imperial thrown. Further, liquidating the Tsar, his children, and his brother did not exhaust the Romanov line, his cousin could and did proclaim himself Emperor-in-exile, and despite being old enough to actually head a restorationist intervention, none materialized. So the notion that killing Alexei was necessary fails to stand up to scrutiny 7.. It is also worth noting as an aside that the Romanovs were deeply unpopular, and to wit, were not the government the Bolshevik revolution occurred under, and supporters of the provisional government (domestic and international alike) formed the overwhelming contingent of the White forces, and the notion that a 14 year old tsarist claimant to the thrown would have had a meaningful impact on that colossal clusterfuck strains credulity.

- It prevented a longterm challenge to Boshevik control in a manner similar to Jacobite uprisings or the Bourbon Restoration.

Taking a more longterm view of the problem, it might be acknowledged that the Alexei presented no immediate threat justifying his liquidation, but, drawing from the history of pre-CIA regime changes, he presented a longterm likely/probable/plausible/possible threat in the form of an eventual challenge, and that acting in light of that possibility was justified if not strictly necessary. If we wish to examine this in light of our moral principles, we need to develop some notion of probability calculus; at what point is taking in innocent life now justified in order to avoid certain possible harms that have a certain probability of occurring. You can formalize this to ridiculous extents8., or you can take the legal systems more qualitative approach, of establish some standard of proof (you are, after all, justifying killing someone), where the execution is deemed justified if seems more likely than not/clearly and convincingly/beyond a reasonable doubt that it will prevent further, greater harm in the future. This lets you weaken the requirement that it is necessary to kill him to merely it is prudent to kill him. What is lacking though is any evidence that anyone has meaningfully carried out this process for any standard beyond plausible. The greatest extent to which this is established is that historically, there have been several restorationist insurrections, but no systematized historical study has been undertaken to quantify the risk of insurrection/coup in the presence or absence of an legitimate claimant.9.

Well perhaps we leave it there; a plausible narrative that places Alexei as the cause of some harm is sufficient in our eyes to justify his liquidation. The problem with this is that it is such a liberal standard that it can be applied to nearly everyone. There are scores of documented peasant rebellions throughout history, so by the same standard it is plausible that any given peasant may be at risk for launching a peasant rebellion down the line and thus, by that same standard, we are justified in liquidating them. Universalizing from this generic peasant^.10. to all peasants. And thus our system named aimed an providing dignity and comfort is able to justify pretty much any atrocity.

- The moral culpability of for the executions lies at the feet of the Tsar who created the system and not the executioners themselves.

This argument goes that it was actually the Tsar that placed him in position to be killed by standing at the top of a monarchical system that has ruined and ended untold numbers of lives. Had the Tsar dismantled that system before it came to blows, Alexei would have lived a happily inbred life as a continental European curiosity.

This argument plays fast an lose with the notion of fault to an extent that borders on the absurd. Within getting into the morass that encompasses the legal notion of fault, I’ll observe that the executioners where in total control of the situation, given the Romanovs were in the zone of immediate material influence, while the Bolshevik leaderships were at a more distant proximity, and Tsar Nicholas II at the head of the Imperial State was a fleeting memory, having greatly influenced the events that now overtook them, but having no control over them. The Bolshevik’s in Ipatiev House or those in leadership in Moscow alone decided who in that house lived and died, they knew that, and they exercised that choice.

- Unpleasant things happen during a revolution and we accept that as soon as they begin.

This is true, but once again, it comes down to the notions of control and proximity. As a leftist, I acknowledge that the struggle for political power may involve the world becoming a worse place (as judged according to my moral principles outline above) due to my actions to make it a better one. This is an abstract acknowledgement. It may also result in me taking actions that I find unpleasant or repugnant11. If it is the moral principles that describe motivate my political struggle though, it is fundamentally self-defeating to exercise my control over my immediate surroundings to knowingly act in a manner that results in an immediate degradation of the world around me (once again, as judged by my moral standards). My actions in the here and now, must be justified according to my principles in the here and now and my actions in the here and now. If 10 minutes ago I was standing in Yekaterinburg and the Whites are closing in, and now I’m still standing in Yekaterinburg and the Whites are still closing in, but now there is a brand new pile of child corpses of my making, then I have made the world a worse place.

No tears for dead peasants

It is reasonable to ask why go to such great lengths to challenge the justifications for the murder of Alexei (which is so emotionally remote to me as to essentially be fictitious). To which I offer the following justifications.

- It’s ridiculous and therefore funny.

- Because eventually some of us may be in positions to make decisions that make the world a substantially better or worse place for others, and I want it be very clear what stands before us when making those decisions. No, none of us are going to decide whether or not an heir lives or dies, but we are going to decide how to treat with those around us, and want everyone to pause before they exercise what little control they have in the world around them before making it a worse place, justifying it with a glib aphorism or some half-baked argument.

1. The fitness for humor here is not considered, as something can be both morally bad and the legitimate target of well-done comedy. Like 9/11.

2. I was promised ice cream if I didn’t say ‘ilk’ here.

3. To wit, one of the main justifications for political violence on the left is that it is directed at those preventing others from enjoying dignity, comfort, or well, life.

4. Such as it is.

5. which we may dub the Yekaterinburg Streetcar Defense

6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Rebellions_in_the_Soviet_Union

7. One could alternatively take the logical form of necessity as a conditional, ~P -> ~Q with P being “the legitimate claimant to the imperial thrown is killed” and “Q” being “the revolution is successful”. Given the contra-factual nature of ~P, the truth value of this statement can’t be evaluated directly, but given the analogous situation in China with PuYi, we can strongly infer that this conditional is in fact false and thus logical necessity is not present.

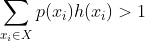

8. define xi to be each enumerated possible future in space X, p(xi) to be the probability of that future occurring, and h(xi) to be the number of lives ruined by Alexei in that future xi. Shoot kid if

9. To reach a preponderance of evidence standard you would need to establish P(Insurrection|Legitimate Claimant) > P(Insurrection), which the strictly materialist interpretation would hold P(Insurrection|Legitimate Claimant) = P(Insurrection).

10 Regular viewers will recognize this as universal generalization.

11 Orwell’s description of the conditions of fighting in the Spanish civil war come to mind.

Alright I was probably gonna make a post about this if you weren’t.

First, I have to say that I’m very surprised at the reaction I’ve seen where a lot of people seem to regard me as a monster for not taking the event that seriously. So I think it’s important to frame it in it’s proper place.

A lot of innocent people died on 9/11. You can say what you will about the bankers but you can’t seriously claim that the firefighters or plane passengers deserved it. This event happened much more recently than the Romanovs, and there are people alive today with real injuries or trauma who could concievably see a post making fun of 9/11. You can say “America deserved 9/11” all day long, but did those specific Americans? I could just as easily say “The Romanovs deserved it” (though perhaps not those specific Romanovs). We can compare the scale of 9/11 to the scale of the Iraq war in the same way we can compare the scale of the dead Romanovs to the scale of WWI and so forth, and we can compare the cringey overreaction to 9/11 to the cringey overreaction to the Romanovs, given for example that Nicholas II was canonized as a saint not all that long ago. So I say that making fun of 9/11 makes you at least 1000 times more of a monster than making fun of the Romanov’s deaths - and yet we (mostly) all do it and make fun of people who take it seriously. So let’s put aside the absurd grandstanding of people calling me a monster or whatever and turn to a more levelheaded discussion of the moral philosophy.

OP’s approach is one that is concerned with justice and legal principles. They contend that it is necessary to establish an objective, scientific study to show that benefit can be derived from killing the Romanovs before it can ever be acceptable to kill them. But when should such a study have been produced? During the war, they were a little busy. Before the war, it’s a little difficult to publish an objective, peer-reviewed paper discussing the merits and flaws of killing the currently living children of the royal family. In general, I find this view that you’re not allowed to estimate probabilities in your head without doing a formal study to be unreasonable and unrealistic.

OP then goes on to describe how if you say it’s OK to murder the Romanovs then you also have to say it’s OK to murder random peasants. As usual with responses to consequentialist approaches, this is extremely trite and can hardly be taken as a serious criticism.

My framework for approaching these questions is quite different. I am only concerned with the consequences of each course of action, with cause and effect. I reject the notion of justice as an end of itself - though I recognize it can sometimes provide a guideline for producing better consequences.

Of course, it is impossible to know beforehand what the consequences of each action will be, which means that you have to constantly rely on your best judgement. Estimation of the likelihood of various events must be made constantly, and often with limited information. If I had to produce scientific studies before saying that an event was probable, I’d be paralyzed with indecision and stuck doing nothing but trying to find and read through scientific studies about which grocery store I should shop at.

Let me use an example here. Should I kill a Nazi? Let’s assume right now I can search online, find someone who is definitely a Nazi, and I can surprise them with a gun and have an almost certain chance of killing them. Well, based on notions of “justice” and “deserving,” maybe I should (not sure what’s stopping you, in that case). But if I look at the consequences of that action, it probably means spending a very long time in prison. However, if I have good reason to think that a specific Nazi is about to do an adventurism against innocent people, then my calculus might go in the other direction. The fact that the Nazi is a bad person is relevant only in how it factors into my calculus and helps me to predict their movements.

When OP suggests that if you start doing calculations like that you’ll end up murdering a bunch of random peasants, I think that’s only because they don’t have experience making calculations or understanding how they work. Obviously, if you murder a random peasant because they might start a revolution, you’ll likely piss off a lot of other peasants and increase the chances of revolution, making it counter-productive and bad by virtually any framework (unless you’re an accelerationist I guess?). Why doesn’t this occur to OP?

It seems to me that OP’s worldview, whether consciously or subconsciously, is influenced by Christian mythology. The goal is to prove you’re a good person so that you can defend yourself at the pearly gates. Meanwhile the devil is constantly tempting us to sin, we are naturally inclined towards evil acts, and so we cannot trust our own judgement to make exceptions to moral rules. If we murder the Romanov children, it is because deep down we want to murder children, and we’re making rationalizations to release the demiurge.

But I reject that framing. I say that I don’t have some beastly urge to murder children that I’m repressing, and I think the same is true of the vast majority of people. I’m not concerned with proving myself at the pearly gates, I’m concerned with producing the best outcomes. I trust my own judgement, which I have cultivated, and I think doing so is unavoidable - even if you defer to others’ judgement or to some principle, it is still your judgement that leads you there.

If you want to argue that the specific choice of murdering the Romanov children was bad, based on what outcomes could be reasonably expected for the action to produce, that’s a conversation we can have. But like you say, it’s not like any of us have royal families in our basement so it’s not the most relevant question, and what it really points to are the differences in our moral frameworks.

You’re absolutely allowed to estimate probabilities in your head without doing a formal study, but when the subject in question is murdering children, you have obligation to be methodical about that process, and to absolutely show your work. Otherwise your are absolutely engaging in the “I had reasonable belief that my life was in danger and thus I acted justifiably in using deadly force” game of modern American policing. Your best judgement after spending 30 seconds mulling over the issue is entirely insufficient. People often have bad judgement, and so when all you need to justify doing something is “someone’s best judgement”, you are setting yourself up for a world of trouble.

I’m getting tired of saying this to people, but show your work. I’m not claiming that you must murder a million peasants just because it’s justified, I’m showing that this standard of reasoning lets you murder any peasant, and so you’re then welcome to deploy this reasoning as a pretext for killing motivated by any other axe to grind. This is adequately demonstrated in history as evidence by what happened to 20,000 polish intellectuals when the soviets rolled through in 1941.

You say things like “likelihood” and “calculation”, but given you can’t point to any actual math or statistics, it seems to me like you’re trying to borrow legitimacy and rigor from these fields, when in fact you really mean “judgements”.

Maybe all the other peasants hated this guy, so in my judgement (not calculation), it doesn’t effect the chance of revolution. So in that case it’s justified?

As a westerner, of course it is, and given that I imagine you’re a westerner too, so is yours. But everything you say after this has no relation to or connection to my position, given that I don’t think there is any such thing as a ‘good’ person or any need to justify oneself in the afterlife.

If I just went out a murdered a child and claimed it was justified, I agree with you that I’d better have a damned good explanation for it when I could’ve just sat at home playing video games. But we’re talking about this in the context of revolution. There were far more important things to consider, and it’s in no way worth the time or energy to contemplete the moral philosophy and historical data for this decision when every day you’re making decisions that affect the life or death of thousands, perhaps even millions of people. In the amount of time you might spend figuring out whether to kill them or not, you might be able to find a marginally better troop deployment that saves 100 people’s lives. Expecting a full on scientific study in that context is pretty absurd imo.

And what about your framework? It’s easy enough to justify harming others when your actions are based on “justice” and “deserving.” On the previous point you mentioned that making snap decisions makes me sound like a police defender, but another police defender line is to argue that a killing was justified because the victim had done something wrong in the past, “They were no angel.” I can point to countless cases in the historical record where violence was argued to be justified on the basis of the moral inferiority of the victims, while ignoring the consequences of said violence.

In reality, anyone can act in bad faith in the context of any moral framework. There’s shitty people who do shitty things and claim cover on the basis of “The ends justify the means” and there’s shitty people who do shitty things and claim cover on the basis of “They deserved it.” You can’t throw out consequentialism just because some people invoke it in bad faith.

I use the words interchangeably, yes. Statisticians don’t have a copyright on the word “likelihood,” sorry.

No, you have to make a full judgement of various factors. If you want to make the case for murdering peasants under a consequentialist framework then I expect you to put more effort into it than that if you want me to seriously engage the question.

It is relevant because I at least find the assumptions I mentioned necessary to understanding your position. I don’t deny that my worldview is influenced by a Christian framework through lingering brainworms I’ve yet to uproot.

I mean if this decision is not that important, not important enough to justify putting to much thought into it, just a throwaway decision, then surely the immediate consequentialist decision is to not shoot the children according to our moral framework. In order to justify shooting the children you have to develop some future spanning narrative, and if you can be bothered to do that, you might as well be bothered to consider the question fully.

I actually agree that this reasoning is unsound, and so I don’t use it (my footnote 3 being it’s close cousin that the victim is currently doing something wrong). I actually wouldn’t have shot any of the Romanov’s, but given that many people here do believe that past misdeeds justify reprisal (we’ll make no excuses for the terror blah blah blah), I didn’t think this would be a side argument worth having.

And there are good people who can be made to do shitty things because someone stands at the ready with a pat, half-baked consequentialist justification for them. This comes up every time liberals want to intervene in some country, and our response to them is the same as my responses in these threads. “Show your work”, in which case their arguments all fall to pierces.

No, but they, probability theorists and logicians are the only ones who can handle them in a formalized way. Everyone else is more or less eyeballing it, which if we’re trying to make decisions that optimize future outcomes seems like exactly the sort of thing you’d want to avoid.

That’s ridiculous.

“Maybe we shouldn’t kill the kids, they weren’t responsible.”

“Yeah, but if we don’t, the monarchists might use them to strengthen their claims.”

End of discussion, versus “Ok let’s go do a historical survey to verify that possibility and also break out the philosophy textbooks.” Your point is incredibly bad faith. It didn’t take a bunch of sitting around theorizing to come up with a justification, it was immediately apparent and easy to express in a single sentence.

This is one of those cases where I literally could not agree with your point even if I wanted to. You’re essentially trying to argue that everyone but the groups you named should forfeit their agency as a moral actor. “Should I ask this person on a date? Better go find a statistician!” Extreme level of field arrogance.

Great, so the standard of evidence required is literally “can anyone say anything in favor of doing this terrible thing” in order for it to be justified, and as soon as that justification is offered, any follow-up questions could be dismissed as “we don’t have time”.

Absolutely not, they are welcome to use whatever systematized thought process they like or none. But if they’re going to engage in fraught moral decision making that have grave consequences for other people, they should absolutely engage in a degree of epistemic humility instead of coming up with some pat 30 second justification for their decision and then insisting to everyone else that they have in fact done their homework.

In that context, yes, as long as it seems reasonable at first glance. The decision wasn’t very important, and they did genuinely did not have time. I’ve already explained how thay context differs from you or me making the same decision.

I really think you have an extremely romanticized view of war and are giving royal lives disproportionate worth.

It was to certain people.

I don’t want to come off as glib, but I think the mistake I am making in some people’s eyes here (not necessarily yours) is that I am giving them any worth.

So was the life of every single individual soldier who died in WWI.

You invoked your field so I’m going to invoke mine. I studied physics and astronomy in uni, and one of the things that helped me with is a better understanding of scale. I’m used to differentiating between very large and very small numbers. For instance, we have a unit called a “barn,” an extremely small area used at the particle scale, because hitting an area of that size is like “hitting the broad side of a barn.” 10^20 and 10^21 are basically identical to most people, even though one is much, much larger than the other. Part of the reason I became a leftist is because after practicing working with numbers like that, I was able to comprehend some inkling of the scale of devastation caused by (for instance) the War on Terror.

I’m sorry but these things need to be considered in the context of scale. If you put as much empathy towards each Russian soldier as you are to the Romanov children, your mind would literally not be able to handle it (nor would mine). Scale and proportionality matter, and in the context of major events like WWI, the evaluation that the lives of 5 children have zero value is probably closer than the value you’re ascribing to them. The difference between say 1/10^7 and zero is too small for the human mind to really comprehend.

I hate moral calculus, but have just a modicum of perspective here: Consider the whole population of the USSR and the catastrophe it would represent not just for most of them but for socialist movements around the world (particularly China) if a little Romanov went on to galvanize opposition. Even if we concede that it’s literally only a 1/1,000,000 chance of happening, that still puts things clearly in favor of killing them because we are talking about many millions of peasants here whose entire lives depend on the Soviets holding out or else being, at best, reduced to basically the status of slavery and deprivation and perhaps all of their descendants for the next century or more as well.

I actually don’t think our moral frameworks are terribly dissimilar (you’ll note my moral principles are framed in explicitly consequential terms). Where there is an appreciable gap though is our epistemic frameworks. You’re using using an ambitious epistemology that gives wide latitude to meaningfully know how ones actions will effect the world, 10, 15, 50 years down the line, and thus they can call upon that knowledge to inform their moral decisions.

My epistemology is much more deflationary. I don’t believe we can meaningfully know how our action affect the world beyond a much narrower time horizon, on the order of weeks in the absence of very well understood and tested dynamical models, and thus we can’t call on long-term future consequences to justify immediate actions. This belief of mine comes from my experience in numerically modelling nonlinear mathematically systems, where trying to nudge the output one way can result in it crashes catastrophically to the other.

I can agree with that framing of our differences. I’m quite comfortable operating in contexts with uncertainty and imperfect information, and I see such things as an inherent fact of life.

If I accept your argument that it’s impossible to predict things “10, 15, 50 years down the road” then obviously I should immediately abandon any notion of revolution. I would fully expect a revolution to make things worse in the short term, and the long term benefits are obviously beyond the scope of precise statistical modelling. I don’t think your approach is tenable or consistent.

There’s a pretty common mistake I see in a lot of contexts where people put too much weight onto factors where it’s easier to gather clean, objective data. Sometimes things that are hard to study can be important too. Just because it’s difficult to produce a study showing whether ending a royal line reduces the probability of counter a revolution doesn’t mean it’s not a reasonable concern.

In a very real sense you should, but not because it’s impossible. Individuals are not the agents of world historical politics in a Marxist system, classes are. You as an individual don’t get to decide if we have a revolution in 15 years or tomorrow, so placing the onus on yourself to achieve revolution is a surefire way to get ineffectual burnout or adventurism.

To borrow from Kuhn’s schema, we live in a time of ‘normal’ politics as opposed to ‘revolutionary’ politics, so our day to day actions as individuals should be grounded in that reality. Thousands of leftists lived and died in Russia decades before the material conditions were right for revolution in '05 or in '17. That doesn’t make their individuals lives useless, but it doesn’t fundamentally limit the amount of change their individual actions could effect.

Do you think that the Bolsheviks used statistical modelling before rising up against the tsar? If not, do you think it was a good decision?

This is probably ancillary to your point, but the Bolshevik’s didn’t really rise up against the tsar, but against the provisional government. Lenin was still in Switzerland when the Tsar was deposed.

The peasants, then.

They were acting in the moment effecting what change they could to improve their conditions and address their concerns at that particular moment. They weren’t attempting to effect or avoid a particularly future event 10-years down the line (a royalist intervention) and weren’t engaged in such morally fraught decision-making (shooting children), so I’m absolutely comfortable with there exercising a lower standard of evidence for justifying their actions.

It took over 5 years of civil war to achieve victory.

The fact that you consider starting a war to be so much “less morally fraught” than shooting a handful of kids during a war is exactly why I keep harping on the fact that you have an extremely naive and romantic notion of what war looks like.

This might be the most absurd thing I’ve seen yet in this struggle session, and considering the comparisons to the bombing of Hiroshima and the War on Terror that’s a very high bar.