We are reading Volumes 1, 2, and 3 in one year. This will repeat yearly until communism is achieved. (Volume IV, often published under the title Theories of Surplus Value, will not be included, but comrades are welcome to set up other bookclubs.) This works out to about 6½ pages a day for a year, 46 pages a week.

I’ll post the readings at the start of each week and @mention anybody interested.

Week 1, Jan 1-7, we are reading Volume 1, Chapter 1 ‘The Commodity’

Discuss the week’s reading in the comments.

Use any translation/edition you like. Marxists.org has the Moore and Aveling translation in various file formats including epub and PDF: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/

Ben Fowkes translation, PDF: http://libgen.is/book/index.php?md5=9C4A100BD61BB2DB9BE26773E4DBC5D

AernaLingus says: I noticed that the linked copy of the Fowkes translation doesn’t have bookmarks, so I took the liberty of adding them myself. You can either download my version with the bookmarks added, or if you’re a bit paranoid (can’t blame ya) and don’t mind some light command line work you can use the same simple script that I did with my formatted plaintext bookmarks to take the PDF from libgen and add the bookmarks yourself.

Resources

(These are not expected reading, these are here to help you if you so choose)

-

Harvey’s guide to reading it: https://www.davidharvey.org/media/Intro_A_Companion_to_Marxs_Capital.pdf

-

A University of Warwick guide to reading it: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/postgraduate/masters/modules/worldlitworldsystems/hotr.marxs_capital.untilp72.pdf

-

Reading Capital with Comrades: A Liberation School podcast series - https://www.liberationschool.org/reading-capital-with-comrades-podcast/

@invalidusernamelol@hexbear.net @Othello@hexbear.net @Pluto@hexbear.net @Lerios@hexbear.net @ComradeRat@hexbear.net @heartheartbreak@hexbear.net @Hohsia@hexbear.net @Kolibri@hexbear.net @star_wraith@hexbear.net @commiewithoutorgans@hexbear.net @Snackuleata@hexbear.net @TovarishTomato@hexbear.net @Erika3sis@hexbear.net @quarrk@hexbear.net @Parsani@hexbear.net @oscardejarjayes@hexbear.net @Beaver@hexbear.net @NoLeftLeftWhereILive@hexbear.net @LaBellaLotta@hexbear.net @professionalduster@hexbear.net @GaveUp@hexbear.net @Dirt_Owl@hexbear.net @Sasuke@hexbear.net @wheresmysurplusvalue@hexbear.net @seeking_perhaps@hexbear.net @boiledfrog@hexbear.net @gaust@hexbear.net @Wertheimer@hexbear.net @666PeaceKeepaGirl@hexbear.net @BountifulEggnog@hexbear.net @PerryBot4000@hexbear.net @PaulSmackage@hexbear.net @420blazeit69@hexbear.net @hexaflexagonbear@hexbear.net @glingorfel@hexbear.net @Palacegalleryratio@hexbear.net @ImOnADiet@lemmygrad.ml @RedWizard@lemmygrad.ml @joaomarrom@hexbear.net @HeavenAndEarth@hexbear.net @impartial_fanboy@hexbear.net @bubbalu@hexbear.net @equinox@hexbear.net @SummerIsTooWarm@hexbear.net @Awoo@hexbear.net @DamarcusArt@lemmygrad.ml @SeventyTwoTrillion@hexbear.net @YearOfTheCommieDesktop@hexbear.net @asnailchosenatrandom@hexbear.net @Stpetergriffonsberg@hexbear.net @Melonius@hexbear.net @Jobasha@hexbear.net @ape@hexbear.net @Maoo@hexbear.net @Professional_Lurker@hexbear.net @featured@hexbear.net @IceWallowCum@hexbear.net @Doubledee@hexbear.net

Decided to go with a new thread per chapter. One big huge thread would have been messy.

Thanks for setting this up. I think we still have to tag comrades in the comments rather than the post for it to show up in their inbox. Unless mine is just being screwy.

Oh no I see now I made a mistake in the syntax of your tag

Can someone else confirm?

I got the other notification, but not this one.

But my name is spelled wrong so that may be why hereEdit: I’m on there twice actually, only one version is misspelled. So I don’t think in post tags work.

I didn’t get notified for this thread, I still only have the notification for the one big one.

Something I always come back to is how unbelievably obvious it becomes that most critics of Marx have never even opened Capital. Just the first like 10 paragraphs are so immediately enlightening to a different way to consider commodities than marginal value and pure exchange value.

I’m just gonna put all my thoughts in comments under this I guess. At least until more discussion arises

So Marx’s definition of Value as residue comes down to this, right (correct me please if I misunderstand, I’ve struggled here a while): We begin with all aspects/materials characteristics of commodities. Subtract all things which are different between commodities (which includes the aspects we could call use-value) and you are left with the common aspects. These aspects are: 1 exchanges value because the commodities still share the ability to be traded with one another and; 2 Value because all commodities were produced by some form of labour power which crystallizes in the commodity.

He calls it residue because exchange values are not inherent but socially determined while the labour power to produce it is inherent to the commodity. Am I missing something here?

For those who went through Western schooling, especially STEM, the method of chapter 1 is confounding because it is the reverse of how we are normally educated. Normally, in math class for example, you are taught an axiom at the start of class, and its truth is demonstrated by a multitude of examples. In science, you are taught a method by which one makes a hypothesis (based on ??? a gut feeling?), and through empirical data collection, its truth is demonstrated.

The line of thought in chapter 1 is the reverse: Marx starts with truths that are self-evident, and infers a logical structure based on that. Observation -> model instead of model -> observation.

So when you refer to a definition of value, keep in mind it’s not an axiom, it was actually a logical inference based on the observation that commodities in actual fact, in reality, are produced for two contradictory purposes, for their use and for their exchangeability. This necessarily implies value, rather than value implying the rest. It also implies that in the real practice of exchange that people identify something common about all commodities, because without such abstraction it would not be possible to resolve the observable exchange relations we see happening.

Thanks for the clear explanation, valuable even if mostly stuff I knew in some terms! I think this misses my question a bit, though. My question is about that “this necessarily implies value”. How is this implication clear in the process of commodity production and trade? Seems he does deduction from all aspects down to some necessary ones, which support and contradict one another, but I was checking if that’s true. Here you seem to indicate instead that it arises after the deduction as a necessary component to explain exchange and use value as they function.

I said “definition” which was definitely the wrong term though. His derivation, I guess, is what I’m getting at.

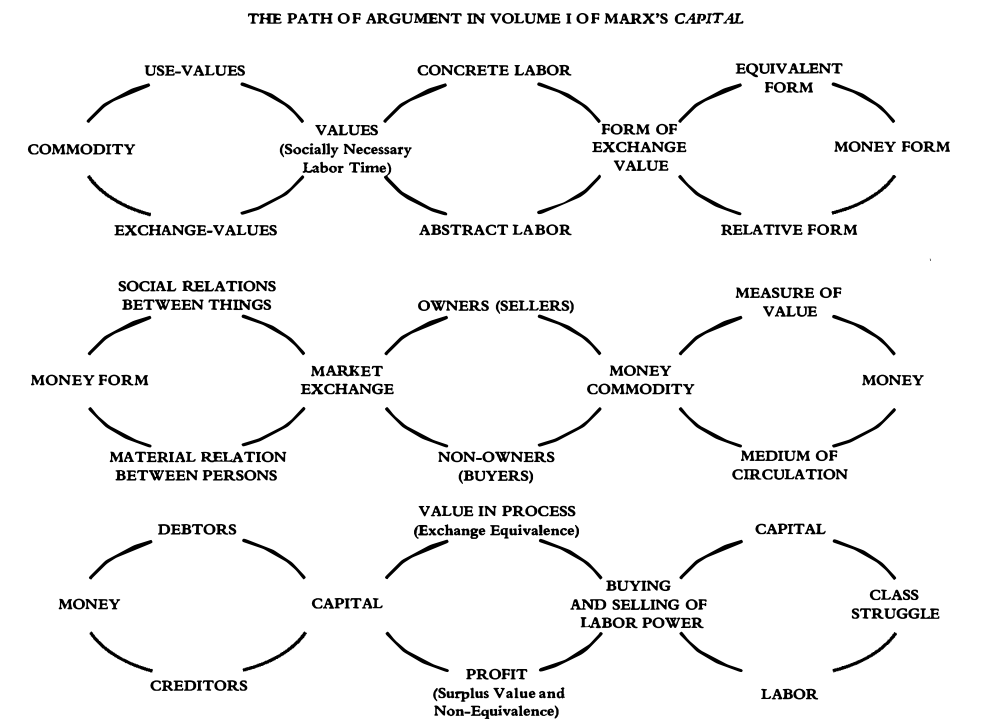

We get to that next. Here’s a diagram from Harvey that I found extremely helpful to understand how Marx structures the work

First we define a commodity, something that is made to be either used or exchanged. Then we kind of shelf use value until we get to defining labor. Then exchange value will be delved into which is where we get to your question. Basically, value comes from comparing the value of this commodity to that commodity, which necessitates the creation of a universal constant, money. One thing that I think about constantly is how alienation is brought about by objectifying and valuing the self, through this constant unconscious process of comparison and evaluating.

Ok thanks again! I think, again, I’m aware that this eventual relation is developed, I was just not sure if this was also what Marx referred to towards the beginning of chapter 1. Seems it was and I just read too much into the paragraph, though, because the “residue” is just later developed more.

One thing I noticed when I read it was that a lot of the things in Capital is stuff I already kind of figured out. I had read Marx before, but like the way that it works is very familiar, as a worker. I never read a book that I felt was written for me, for us as much as this one. The difference is that where I had a notion of a concept or relationship, Marx has a proof of it; where I had an understanding, Marx goes much, much deeper with historical examples and tables and insight (often interwoven with references to all manner of classic literature and philosophy, the magic is in the notes.) I went into this book expecting to learn an economic theory, but what I really gleaned from it was a method of critique

I recently read Spinoza’s Ethics, and its ordered very similar. It starts with the most basic provable material claims, and from that (not without some liberties) constructs an entire system of ethics and human nature by building, staking provable facts one on top of another, the conclusions are constructed meticulously. It also starts very dry and difficult. Marx is taking it so much further because he is trying to make sure that bourgeois economists can’t say “Marx never considered x.” Its a lot of ground to cover though. And it takes a little patience. There is a ton of value in the detail esp in the later chapters.

Anyway I’m excited for more people to read and learn from this incredible work, just being a nerd over here thanks for humoring me

I got hung up on that question as well, and so have many other people, especially critics like Bortkiewicz. It isn’t helped by David Harvey in his book saying that it is a “cryptic assertion” that the substance of value is abstract labor.

If value is an assertion, then it can be taken on faith or dismissed with as little reason.

First is recognizing that there must be a third thing if qualitatively different things, in different quantities, are compared quantitatively. In section 3 Marx cites Aristotle on this. Strictly speaking it is logically invalid to say “1 table is equal to 3 chairs” because they are different things. What is unsaid in that statement is “some common substance/property between 1 table and 3 chairs is present in equal quantity”. So it implies both qualitative equivalence (same substance) and quantitative equivalence of some third thing.

At this point it’s unclear why Marx singles out labor… let’s see what he thought about this “cryptic assertion”:

What Marx had to say about it

”Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish. Every child knows, too, that the masses of products corresponding to the different needs required different and quantitatively determined masses of the total labor of society. That this necessity of the distribution of social labor in definite proportions cannot possibly be done away with by a particular form of social production but can only change the mode of its appearance , is self-evident. No natural laws can be done away with. What can change in historically different circumstances is only the form in which these laws assert themselves. And the form in which this proportional distribution of labor asserts itself, in the state of society where the interconnection of social labor is manifested in the private exchange of the individual products of labor, is precisely the exchange value of these products.

Science consists precisely in demonstrating how the law of value asserts itself. So that if one wanted at the very beginning to “explain” all the phenomenon which seemingly contradict that law, one would have to present science before science.”

If the substance of value being labor was a speculative assertion, then someone else could suggest something else common to all commodities (and many have) such as that they all contain energy, or they are all abstractly useful.

But labor being that common thing is not speculation, it is a prerequisite for a society in which there is a division of labor among independent producers, where exchange of products mediates the exchange of private concrete labors.

Uhhh… Let me be 30 yards of linen

TAN COAT

Just a word of encouragement to anyone struggling with chapter 1, the first three chapters (and chapter 1 especially) of Capital are notoriously heavy and hard to read. Marx and Engles both apologised for them! It’s not just you, you’re not lacking some quality, everyone finds the first 3 chapters tough. So don’t worry, go steady, get through them, especially if it’s your first Marxist reading. These chapters will make more sense retrospectively once you’ve seen how his arguments develop through the book(s). Some people (not me) even recommend reading the book out of order to get more from these chapters later on.

This is what I am trying to keep in mind. This is also a reason why I don’t really have much to say on it this week yet. I feel like thoughts are just starting to form. The parts about money for example are very thought provoking and have lead to some side-reading as well, but I can’t form any coherent thoughts from them just yet.

I am trying to take this as a sort of primer and trust the process, very much appreciate the comments here as they help in forming thoughts about it a lot.

Chapter 1 Section 3 kicked my ass lol

Fun game! How many common “refutations” of Marxism, the kind you might find in r/neoliberal, are directly addressed in the first chapter, especially in the first few pages of Capital.

Refutations of the labor theory of value often start with a claim that LTV means that if a laborer slacks off and is super inefficient in their production, that this will somehow make the commodity they produce more valuable. Another version of this argument is the claim that LTV means that the quality of the commodity doesn’t affect it’s value, or that literally useless commodities are supposed to have value.

If these people have read Capital, they didn’t get past the first 3 paragraphs, because paragraph 4 is where the discussion of use value begins. It turns out, surprise, commodities actually have to be useful to people and of usable quality to have value, they don’t just magically gain value because someone spent a lot of labor on processing or manufacturing it. A few paragraphs later, we get to discussions about the average labor power of society, and how that correlates to prices of exchange. I think what people get backwards about LVT is that, yes, inefficient productivity CAN cause a commodity to be very valuable and have a high price, but only when the average amount of labor required to produce or extract it is very high.

Marx’s example of diamond extraction is prescient: diamonds were legitimately quite difficult to extract from the earth in that era, and so their value was high. In our modern age, automation in mining and synthetic diamond production have dramatically increased the productivity of labor of diamond mining, which has made them much less valuable. That’s not because any particular worker was working super slowly and inefficiently, nor is it because of the use value of diamonds decreased (their use value has arguably increased, as they’ve found applications in industrial processes).

(I think it’s not until vol 3 that Marx talks about monopolies, but that’s an obvious elephant in the room when talking about diamonds)

Omg that link is so incredibly econ brained. It’s like bourg academic economists have to write garbage like this to prove they haven’t read Marx.

Marx’s formulation of LTV is explicitly that what is contained in value isn’t labor, it is labor power. It isn’t just work, it is working for the capitalist. Power is energy exerted over time, allowing us to determine the actual material composition of value which eludes the bourgeois economist and their idealistic and transparently useless equilibrium pricing. Marx teaches while bourg economics obfuscates. He is explicit and repetitive, which makes us truly consider the “stuff” of value. This is why liberals can’t tell the difference between mercantilism and capitalism. Value is our time and energy, our limited renewable life taken out of us, much of which is unpaid, and converted into commodities which converts to profits for the capitalist. Private property has never been anything but a grift, a way to trick the masses into voluntarily surrendering our material bodies for a dream sold to us by parasites.

Capitalism is class oppression, if it wasn’t it wouldn’t create value, it would just shift it around like medieval mercantilism. Honestly I think this is where a lot of progressive liberal “Marxists” end up in an overly economistic interpretation, especially class reductionist tendencies. Misreadings of Marx lead to bourgeois economic obfuscation; a close reading of Capital gives us the basic formulations for dispensing with bourgeois economics for good.

The other key thing to note is that commodities are not valued around the individual circumstances of their creation. So if I decide to make a perfect copy of a ‘bic biro’ pen, without the aid of specialist tooling and experience, it would take me hundreds of hours to make a biro, but the socially necessary labour for making a bic is the mere seconds of labour that a biro takes on the bic production line. The individual circumstance of the creation of my hand made biro doesn’t affect the value of the commodity.

“Jacob doubts whether gold has ever been paid for at its full value. This applies still more to diamonds. According to Eschwege, the total produce of the Brazilian diamond mines for the eighty years, ending in 1823, had not realised the price of one-and-a-half years’ average produce of the sugar and coffee plantations of the same country, although the diamonds cost much more labour, and therefore represented more value. With richer mines, the same quantity of labour would embody itself in more diamonds, and their value would fall. If we could succeed at a small expenditure of labour, in converting carbon into diamonds, their value might fall below that of bricks.”

This paragraph is like a three in one:

"Some people might think that if the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of labour spent on it, the more idle and unskilful the labourer, the more valuable would his commodity be, because more time would be required in its production. The labour, however, that forms the substance of value, is homogeneous human labour, expenditure of one uniform labour power. The total labour power of society, which is embodied in the sum total of the values of all commodities produced by that society, counts here as one homogeneous mass of human labour power, composed though it be of innumerable individual units. Each of these units is the same as any other, so far as it has the character of the average labour power of society, and takes effect as such; that is, so far as it requires for producing a commodity, no more time than is needed on an average, no more than is socially necessary. The labour time socially necessary is that required to produce an article under the normal conditions of production, and with the average degree of skill and intensity prevalent at the time. The introduction of power-looms into England probably reduced by one-half the labour required to weave a given quantity of yarn into cloth. The hand-loom weavers, as a matter of fact, continued to require the same time as before; but for all that, the product of one hour of their labour represented after the change only half an hour’s social labour, and consequently fell to one-half its former value. "

I read section 2 and like couldn’t make much sense of it that It feels like I forgot everything in section 2, like I didn’t read it at all, and it feels very embarrassing. I know I’m gonna have to reread it just like, got very abstract? At least for section 1 there are things that I could latch onto that like brings it all together? if that makes sense.

also in section 1, I really liked that Marx brought up diamonds in one of his examples since like that very relevant today, mainly with like artificial diamonds

Marx’s writing style is perfect for getting in that reading zone where you aren’t really internalizing anything but your brain is going over the words and telling you that you read them.

It’s helpful to stop just about every sentence and ask, “what does that mean?”

reading zone where you aren’t really internalizing anything but your brain is going over the words and telling you that you read them

I have to make notes, particularly in my own words rather than just transcribing, while reading basically any book that isn’t fiction or I just enter that mode. Makes it considerably slower to get through, but I figure that the time I lose during is made up for not having to re-read it every few years to remember what’s being said.

This is a good strategy!

I’ll try doing that, I’m also thinking of just reading on and then coming back to that section as well and see if it makes any better sense

Just FYI, you gotta make a comment with all the @ names to ping your list of users to your post.

@invalidusernamelol@hexbear.net @Othello@hexbear.net @Pluto@hexbear.net @Lerios@hexbear.net @ComradeRat@hexbear.net @heartheartbreak@hexbear.net @Hohsia@hexbear.net @Kolibri@hexbear.net @star_wraith@hexbear.net @commiewithoutorgans@hexbear.net @Snackuleata@hexbear.net @TovarishTomato@hexbear.net @Erika3sis@hexbear.net @quarrk@hexbear.net @Parsani@hexbear.net @oscardejarjayes@hexbear.net @Beaver@hexbear.net @NoLeftLeftWhereILive@hexbear.net @LaBellaLotta@hexbear.net @professionalduster@hexbear.net @GaveUp@hexbear.net @Dirt_Owl@hexbear.net @Sasuke@hexbear.net @wheresmysurplusvalue@hexbear.net @seeking_perhaps@hexbear.net @boiledfrog@hexbear.net @gaust@hexbear.net @Wertheimer@hexbear.net @666PeaceKeepaGirl@hexbear.net @BountifulEggnog@hexbear.net @PerryBot4000@hexbear.net @PaulSmackage@hexbear.net @420blazeit69@hexbear.net @hexaflexagonbear@hexbear.net @glingorfel@hexbear.net @Palacegalleryratio@hexbear.net @ImOnADiet@lemmygrad.ml @RedWizard@lemmygrad.ml joaomarrom@hexbear.net HeavenAndEarth@hexbear.net impartial_fanboy@hexbear.net bubbalu@hexbear.net equinox@hexbear.net

I promise I will do this! No more lazy owl!

Roast of the Week™ — Chapter One Edition

brought to you by Starbucks

“Truly comical is M. Bastiat, who imagines that the ancient Greeks and Romans lived by plunder alone. But when people plunder for centuries, there must always be something at hand for them to seize; the objects of plunder must be continually reproduced. It would thus appear that even Greeks and Romans had some process of production, consequently, an economy, which just as much constituted the material basis of their world, as bourgeois economy constitutes that of our modern world. Or perhaps Bastiat means, that a mode of production based on slavery is based on a system of plunder. In that case he treads on dangerous ground. If a giant thinker like Aristotle erred in his appreciation of slave labour, why should a dwarf economist like Bastiat be right in his appreciation of wage labour?” — Karl Marx, Capital vol 1, ch 1, footnote 34

:dwarf-economist:

this roast of the week idea is awesome

Hey, can you add me to the tag list? Thanks for organizing this

Done

Chapter 1 has been quite the trip. Difficult but very interesting and rewarding to grapple with. The commodity fetishism chapter is quite the finish.

P. S. It would be nice if the site mods stickied this on the front page to make it easier to find and drive more traffic to it.

It was up front a day or two ago, then it must have been unlinked or something.

I noticed that the linked copy of the Fowkes translation doesn’t have bookmarks, so I took the liberty of adding them myself. You can either download my version with the bookmarks added, or if you’re a bit paranoid (can’t blame ya) and don’t mind some light command line work you can use the same simple script that I did with my formatted plaintext bookmarks to take the PDF from libgen and add the bookmarks yourself.

If the download expires or you notice any errors with the bookmarks please let me know and I’ll take care of it!

“A sugar-loaf being a body, is heavy, and therefore has weight: but we can neither see nor touch this weight. We can then take various pieces of iron, whose weight has been determined beforehand. The iron, as iron, is no more the form of manifestation of weight, than is the sugar-loaf. Nevertheless, in order to express the sugar-loaf as so much weight, we put it into a weight-relation with the iron. In this relation, the iron officiates as a body representing nothing but weight. A certain quantity of iron therefore serves as the measure of the sugar, and represents, in relation to the sugar-loaf, weight embodied, the form of manifestation of weight. This part is played by iron only within this relation, into which the sugar or any other body, whose weight has to be determined, enters with the iron. Were they not both heavy, they could not enter into this relation, and the one could therefore not serve as the expression of the weight of the other. When we throw both into the scales, we see in reality, that as weight they are the same, and that, therefore, when taken in proper proportions, they have the same weight.”

“A sugar-loaf being a body, is heavy, and therefore has weight: but we can neither see nor touch this weight. We can then take various pieces of iron, whose weight has been determined beforehand. The iron, as iron, is no more the form of manifestation of weight, than is the sugar-loaf. Nevertheless, in order to express the sugar-loaf as so much weight, we put it into a weight-relation with the iron. In this relation, the iron officiates as a body representing nothing but weight. A certain quantity of iron therefore serves as the measure of the sugar, and represents, in relation to the sugar-loaf, weight embodied, the form of manifestation of weight. This part is played by iron only within this relation, into which the sugar or any other body, whose weight has to be determined, enters with the iron. Were they not both heavy, they could not enter into this relation, and the one could therefore not serve as the expression of the weight of the other. When we throw both into the scales, we see in reality, that as weight they are the same, and that, therefore, when taken in proper proportions, they have the same weight.” “bu’ iron’s hééviuh than sugar…”

“bu’ iron’s hééviuh than sugar…”Notes – Chapter 1

Not comprehensive or a replacement for reading. My personal highlights and emphases based on my thoughts while reading.

I will add section summaries as replies to this comment. Edit: okay this was a lot more work than I expected, let me know if you want more, otherwise I’m probably gonna stop

Section 1: The Two Factors of a Commodity: Use-Value and Value

There are two essential components of the commodity, value and use-value.

- Use-value is the concrete, natural form of the commodity; its physical or measurable characteristics. Quality and quantity are determined by direct physical observation.

- Value is the abstract, social form of the commodity. Its quality or substance is homogeneous, abstract human labor. Its quantity is socially necessary labor time (SNLT).

We infer value through exchange value, the relationship between two commodities such as “one shirt is worth two hats.”

Mass and weight provide an almost 1-to-1 analogy to value and exchange value, respectively. Objects have mass, but we do not measure absolute mass. We always measure relative mass by comparing the mass of two objects. One of these objects might be a standard kilogram weight. So weight expresses mass, it allows us access to it, but only through relative measurements of different massive objects. When weighing a mass, all other properties besides mass are ignored; color, volume, texture, etc. do not affect the weight. All other qualities except mass are “abstracted” away, and the objects are considered only insofar as they are masses.

Like the above, exchange value expresses value, but only after abstracting away all the distinct characteristics (use value) of the commodities. When we abstract from the use-value of a commodity, we also abstract from the concrete kind of the labor that produced it. This leaves a “residue” of abstract labor, human labor as such. This is the substance that forms value, common to all commodities.

Exchange value tells us about equivalence in terms of both quantity and quality. It is only logical to compare two quantities if they are of like quality. Think of it like converting to the right “units” to add two lengths: You can’t directly add 5 inches + 3 centimeters, so you convert one into the units of the other in order to add them as quantities of the same substance.

Section 2: The two-fold Character of the Labour Embodied in Commodities

When we abstract from the use-value of a commodity, we also abstract from the concrete kind of the labor that produced it. This leaves a “residue” of abstract labor, human labor as such. This is the substance that forms value, common to all commodities.

This is a small point, but this dichotomy between concrete/natural, abstract/social continues throughout Capital in various forms.

Marx’s method is not like the modern scientific method in which one test an arbitrary hypothesis. Here, the hypothesis (or thesis, more properly) is identified by the internal logic of the object of analysis (here, the commodity). This immanent critique is one example of Hegel’s influence on Marx. The reason this is important: Chapter 1 is not a hypothetical or a final model to accept or deny (like a marginal utility theory, e.g.). It is a set of observations first and foremost, with logical inferences in tow.

okay this was a lot more work than I expected, let me know if you want more, otherwise I’m probably gonna stop

Your summaries are very helpful!

Section 3: The Form of Value or Exchange Value

The purpose of section 3 is to trace the “genesis” of money, from exchange value to “the dazzling money-form.”

In all subsections, a value relation is any relation that manages to express, or reveal, the value of a single commodity.

A. Elementary or Accidental Form Of Value

x commodity A = y commodity B

The left side of the equation is the relative form, the commodity that has its value expressed. The right side of the equation is the equivalent form, the commodity that expresses value by acting as an equivalent.

This elementary form of value is symmetrical, so reading it either direction is equally valid and merely a different perspective; but in either case, only one or the other commodity expresses its value.

The equation implies equivalence of both quantity and quality. The word for this ability to compare quantity, by virtue of identical quality, is commensurability. The value of the relative-form commodity takes on an existence in the bodily form, in the use value, of the equivalent-form commodity. This sounds really odd, but think of it like mentally substituting “y commodity B” everywhere you see “x commodity A”, not just in quantity, but in quality too. The physical body of commodity B gives a physical, independent existence for the purely social value-substance from our analysis which is imprisoned inside the use value of commodity A.

Think about the consequence of value taking on the physical form of the equivalent-form commodity (the coat in Marx’s example). If the physical body of a commodity is value itself, in the context of a single elementary value relation, can you guess what commodity might be universally recognized as value?

Finally, because value relations are relative, they do not tell us the absolute amount of value in a commodity. If commodities A and B both dropped in value by half, they would still happily exchange at a rate of x to y respectively.

The physical body of commodity B gives a physical, independent existence for the purely social value-substance from our analysis which is imprisoned inside the use value of commodity A.

This was a part which I kept getting hung up on. It seems so straightforward but the way it is worded in Capital, and a bit here too, is difficult for me to fully intellectualize for some reason. The analogy Marx gives of “weighing” makes it pretty clear, so I don’t understand why I find it so complicated lol

Yeah it’s pretty weird and still gives me trouble. Some of these more nuanced points aren’t that important for following the book. The points still matter but they aren’t necessary for understanding exploitation.

It seems like you have a pretty solid understanding of chapter 1 so far, as well as anyone else at least. It’s a chapter that makes more sense when you return to it after finishing the book, or even years later after reading other stuff.

It’s why I recommend reading volume 4 (theories of surplus value) after volume 1. It is Marx’s notes on all the major political economists, contextualizing their theories in terms of his own, in order to explain where they got stuck or went wrong. It’s invaluable for understanding the esoteric points in volume 1. Often they were born of arguments he had in the past, or realizations about subtle missteps that other economists made.

Also, volume 2 is far drier in tone, and has a lot more computation. So many people give up there. To be honest I mostly skimmed volume 2, it was too painful lol.

Chapter 2 next week should be a breeze. It’s not too complicated and only a few pages. So that should give us all time to pause and let some questions percolate.

It’s why I recommend reading volume 4 (theories of surplus value) after volume 1. It is Marx’s notes on all the major political economists, contextualizing their theories in terms of his own, in order to explain where they got stuck or went wrong. It’s invaluable for understanding the esoteric points in volume 1. Often they were born of arguments he had in the past, or realizations about subtle missteps that other economists made.

Yeah that makes sense, the footnotes where he directly critiques classical political economy are interesting. I’m not very well read on this, so seeing how Marx understand his own project as different from what came before is a bit obscure for me right now.

Also, volume 2 is far drier in tone, and has a lot more computation. So many people give up there. To be honest I mostly skimmed volume 2, it was too painful lol.

My only exposure to it are through secondary sources dealing with the different “circuits”. Looking forward to it lol

Chapter 2 next week should be a breeze. It’s not too complicated and only a few pages. So that should give us all time to pause and let some questions percolate.

So so much shorter lol, I feel like we could have split chapter 1 into two parts

Section 4: The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof

Honestly this is one of my favorite sections of the entire book, and it’s right at the start. Many Marxists, and even some non-Marxist, humanist types, have noted the significance of commodity fetishism and more broadly Marx’s theory of alienation. It goes beyond capital, but it is certainly interesting in regard to capital too!

Definition of commodity fetishism:

“In order, therefore, to find an analogy, we must have recourse to the mist-enveloped regions of the religious world. In that world the productions of the human brain appear as independent beings endowed with life, and entering into relation both with one another and the human race. So it is in the world of commodities with the products of men’s hands. This I call the Fetishism which attaches itself to the products of labour, so soon as they are produced as commodities, and which is therefore inseparable from the production of commodities.”

In other words,

“the relations connecting the labour of one individual with that of the rest appear, not as direct social relations between individuals at work, but as what they really are, material relations between persons and social relations between things.”

I think the name “fetish” is perfect. It refers to religious fetishes — think voodoo dolls and other idols — which humans consciously produce, yet they believe that the objects take on a supernatural character once produced.

The name is perfect for two reasons. First, it very precisely describes what is happening with commodities and the illusions they produce in the mind. Second, because it is a jab at the colonizing European societies that believed themselves to be so culturally and intellectually superior to the peoples they colonized, many of whom used fetishes in their religious practices.

“… the mutual relations of the producers, within which the social character of their labour affirms itself, take the form of a social relation between the products.”

This line reminds me of one of Marx’s letters to his friend Ludwig Kugelmann in which he strongly defends his identification of labor as the substance of value. For Marx, the procedure for this determination is backward from the political economists. The political economists started from the commodity in order to identify the determinants of commodity prices. From this point of view, labor is just one speculative guess at one such determinant among many, such as energy, utility, etc.

Marx starts from the other direction. For him the big question is not what forms price magnitudes? but rather how does capitalist society distribute labor? And, as he says in the letter, it is clear that the way that the total social labor is distributed in capitalism is through the exchange of commodities. From this perspective it is no longer a mystery why labor is the essence of value.

To digress a tad. Alienation occurs when a human power or ability is placed onto an object. This occurs with labor being objectified (i.e. placed into an object) as value. But it can occur in other ways, such as placing our legal-political power into liberal institutions. We are alienated from our ability to affect political decisions and only have access to that ability through electoral institutions.

The same is true for the “human essence” which I won’t spend time exploring here; but in Marx’s early, pre-communist 20s and 30s, when he was involved with the Young Hegelians, he spent a lot of time thinking about materialism and religion in works like Theses on Feuerbach, The German Ideology, and Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. In the intro to the last one, where Marx makes his famous “opiate of the people” line (this intro is my favorite of all of Marx’s writing) he talks about “inverted consciousness” in an “inverted world”. This inversion is due to alienation, and in that way is linked to commodity fetishism.

Section 3 (continued): The Form of Value or Exchange Value

B. Total or Expanded Form of value

z Com. A = u Com. B or = v Com. C or = w Com. D or = Com. E or = &c.

Generalization of the elementary form of value from subsection A. Each singular commodity A has an elementary form of value with each other commodity B, C, D, etc. and vice versa. It’s unwieldy to state an infinite series, but at this point it is the only way to adequately express the value of a commodity.

C. The General Form of Value

Since the expanded form of value is unwieldy, simply flip it around, since we already knew in subsection A that reading the equations backward is equally valid. Instead of each commodity requiring an infinite series of elementary value relations to express its value, read it as all commodities being able to express their value universally in one special commodity Z. This one commodity takes on a special social function of embodying value universally. This becomes its use value.

The universal equivalent commodity only emerges insofar as all other commodities are practically excluded from direct exchange. Although as a logical prerequisite all commodities are directly exchangeable with each other, in practice they exchange only directly with the universal equivalent, and it the mutual exchangeability of all commodities is apt to be “forgotten”. Thus we perceive exchangeability to be unique to that one commodity, as if there is something inherently special about that one commodity in itself, when its specialness is precisely because of it being “just” a regular commodity, at first.

D. The Money-Form

Same as form C, but note that historically gold has been chosen as the universal equivalent commodity.

I am hung up on the difference between the labor theory of value and “supply and demand” from school.

In Marx’s example of the corn out of season I understand the labor value is higher, but how is this different from saying less supply yields higher price?

Likewise with the loom example, the powered loom devalues the labor value but it could also be understood as an increase in supply per unit labor.

Is it the same concept framed differently or am I missing something?

So, both the labor theory of value and “supply and demand” can both coexist in Marx’s framework. They are compatible ideas. On the most basic level, cloth from a loom has a “use value.” I can take the cloth and use it as a towel or a wash-cloth. Or, I can take the cloth, cut it up, and sew it together into a shirt, pants, etc. This “use value” is what basically determines the “demand” part of supply and demand. The “supply” part of supply and demand is basically determined by the labor that goes into making a thing. Someone has to plant the cotton, pick it, put it on the loom, dye it, transport it, sell it at the market, etc.

So, the higher a “use value” is, the higher the demand can be. And the more labor that has to go into making something, the lower the “supply” will be. This is a big, big oversimplification, of course. But to continue the cloth example, if you look at high-quality, durable blue jeans vs. a simple washcloth, the blue jeans have more “use value” to you as a consumer, so they can have a higher demand, increasing their price. You can then take the basic “use value” of the blue jeans and find its “exchange value” by looking at all sort of different things, including advertising, artificial scarcity, etc., which affect demand, and things like labor laws, monopolization, transportation infrastructure, etc. which affect supply.

The main difference between “exchange value” and price is that “exchange value” is independent of many complicating factors affecting price, like currency exchange rates, geographical differences in standard of living, etc. For example, the same blue jeans, with the exact same “use value” and “exchange value,” might be sold at a higher price in New York City than Boise, Idaho, because people there are willing to pay more money for the same jeans. In a more online example, the exact same video game is sold at wildly different prices in different countries with different currencies. Discounts and sales affect prices even more drastically. But the existence of a coupon/discount does not change the “use value” of a game, or even its abstract “exchange value,” just the price you pay for it.

This is actually a very subtle issue, with a lot of complicated details to work through. Here an entry about it from the literal “Encyclopedia of Marxism:”

Exchange-value differs from “price” in two ways: firstly, price is the actualisation of exchange-value, differing from one exchange to the next in response to a myriad of factors affecting the activity of exchange; secondly, price is the specific value-form, measuring the value of the commodity against money.

But to sum it up, Marx does believe in “supply and demand,” which is perfectly compatible with the labor theory of value. It’s just that labor determines the “supply” side of supply and demand. Because it is laborers who are ultimately “supplying” the raw materials, and the labor that goes into turning those raw materials into usable commodities. Hope this helps!

This is very helpful thank you. I realize now that I was conflating price and exchange value - you’re right, it’s a subtle but important difference that I breezed over

This explanation has “use-value” in quotations and is clearly simplified for explanatory purposes. I understand it wasn’t meant to be fully precise. But I think it gives a wrong impression of use value.

Use value is not synonymous with abstract usefulness and it isn’t a quantity. It’s more like a true/false, a product either is or is not a use value, depending on whether it is actually consumed. And of course we should always keep in mind we are talking of mass-produced commodities, not one-off works of art. If a commodity is regularly produced and consumed, in short, if there is an industry for it, it is a use value.

Whether something is a use value does not depend on the degree or magnitude of its usefulness, but exclusively on the fact that it has particular physical, chemical, aesthetic, or other properties that allow it to be useful. So in Capital, use value is more properly understood as the qualitative description of a commodity, like “red” or “nutritious”. The physical form of an apple is itself the use-value of an apple. The physical quantity of apples is the quantity of its use-value.

Let me know if you disagree, I’m open to discussion.

So in Capital, use value is more properly understood as the qualitative description of a commodity, like “red” or “nutritious”.

Yes, I agree with this. I think one of the reasons Marx separates Use Value and Exchange Value is to examine the basic “atom” of the economy - the commodity - through two different lenses, the qualitative and quantitative lenses. Use Value is a qualitative way of looking at a commodity, and Exchange Value is a quantitative way of looking at it. And Marx is asking us, as readers, to consider the Use Value, Exchange Value, and the actual price we pay for the commodities we use in our everyday lives, to try to get us to examine the world around us in a more critical way.

Use value is not synonymous with abstract usefulness and it isn’t a quantity. It’s more like a true/false, a product either is or is not a use value, depending on whether it is actually consumed.

I’m no expert, but I think there is some additional nuance. A cork screw and a bottle of wine both have use-values, even though one is consumed through its use while the other is not. I don’t think consumption is key here. Though if you add the derivative of time, you could argue the cork screw is being consumed for a period of time - Engles cannot open a bottle of wine with the cork screw if it is currently being used by Marx to do the same.

While this example is silly, it can have more profound implications if we think about time spent in the context of production. If it takes a machine tool five minutes to make a nut and ten minutes to make a screw, it cannot make both 12 nuts and 6 screws within the same hour-long slice of time.

I think it is also worth highlighting the non-fungibility of use-values. Not that objects simply have or do not have use-values, but that use-values are unique and concrete. A saw has a use-value and a hammer has a use-value, but at the level of use-values, one cannot substitute another. This requires the introduction of value in abstract as you point out.

Consumption makes more sense when viewed in the aggregate of society. A corkscrew industry presupposes the social need for not only producing, but reproducing corkscrews on a regular basis, depending on the rate of consumption. Corkscrews have a limited lifespan due to corrosion, dulling, breaking apart, being lost, etc. which results in some definite number of corkscrews needing to be produced regularly for replacement, in addition to first-time consumers. In this view, you can think of consumption occurring piecemeal each time a corkscrew is used, just like a machine is used up a little bit each time it is used before eventually needing to be replaced.

I agree with your point on fungibility, although I think it is more accurately termed commensurability. At least, the latter is the term Marx uses. All commodities are fungible, meaning a commodity of type A is interchangeable with another commodity A. They are indistinguishable as instances of the same commodity. However, different use-values are of different quality as use-values and therefore incommensurate, not directly able to be compared quantitatively without a “third thing” common to both. They are different as use-value and the same as value.

When I say use-value is a boolean, I’m talking about one step up in abstraction. A commodity is “a” use-value, and its use value is its physical characteristics which are sought for consumption. Although commodities A and B are different use-values, they are both the same in that they are use-values, and therefore can be exchanged.

Edit: the other answer is better, but I’m going to leave this up in the hope someone can either confirm or deny what I said in the last paragraph.

Likewise with the loom example, the powered loom devalues the labor value but it could also be understood as an increase in supply per unit labor.

(I can take a stab at this one, but someone please correct me if I am wrong.)

What you describe is whats happening. If the necessary labor time to produce one yard of linen is cut in half, one unit of labour produces 2x the use-value/material wealth compared to yesterday’s hand loom, but is now worth 1/2 per unit produced in exchange. So the material wealth increases, but at the same time the value of each yard of linen diminishes.

If I’m understanding this, this is the way the dual character of labor relates and forms the dual character of the commodity-form. I. E. Concrete labor as production of use value (and material wealth) and abstract labor as the amount of average necessary labor time (and thus value).

Thank you 🙂

could someone help me understand what is meant by the ‘dual character of labour’?

The big term that he’s getting at there is ‘social labor’ which is the form of labor that occurs within capitalist production (and socialist production).

Individual labor creates, as quarrk pointed out, use value. Something that is produced to be immediately consumed. Social labor produces exchange value, something that is means not to be immediately used, but to be exchanged for something else.

The thing with exchange value is that under capitalist production, the capitalist controls the exchange and the laborers only receive a portion of the exchange value they produce. So this ‘dual character’ of labor ends up feeding into the primary contradiction of capitalism which is wage labor.

The appendix on the value form might be helpful.

”The analysis of the commodity has shown that it is something twofold, use-value and value. Hence in order for a thing to possess commodity-form, it must possess a twofold form, the form of a use-value and the form of value. The form of use-value is the form of the commodity’s body itself, iron, linen, etc., its tangible, sensible form of existence. This is the natural form (Naturalform) of the commodity. As opposed to this the value-form (Wertform) of the commodity is its social form.”

If commodities have a two-fold form, then there is correspondingly a two-fold form of the labor that produces them.

Just as commodities are viewed abstractly (via real exchange relations) as uniform value, abstracted from use-value, so also is the labor that produces value seen as a homogeneous human labor, abstracted from the particular trade or type of labor. Likewise, the type of labor that produces use-values or particular types of commodities, is itself a concrete labor of a definite kind like cotton spinning, baking, metalworking, etc.

Concrete labor produces concrete use values.

Abstract labor produces value.